Jan Kaplický: architect of dizzying and inspirational visions

Time runs fast. It has been over a month since the architect Jan Kaplický died in Prague, on 13 January 2009. Everyone who had ever met him was probably thinking about him at that time. Almost everyone described him as an excellent architect and his death as a great loss for Czech as well as global architecture. I don’t mean to question these evaluations. Jan Kaplický’s professional abilities are undisputable. However, if we take architecture as an activity resulting, as its output, in a building, a real and usable building, in case of Jan Kaplický we come to a result surprisingly unsizeable.

Jan Kaplický is rightfully described as a very talented architect of a visionary type, whose work was always ahead, who dazzled, charmed and inspired. His exceptional career was signalled by its very beginnings, and Kaplický’s situation was not definitely easy, being an immigrant to the United Kingdom. He started in Denys Lasdun’s studio, then worked for the Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ studio, participated in the project of Centre Pompidou in Paris (in Paris, however, he did not continue in his work on this project; allegedly the absence of a UK passport prevented him); later he also cooperated with Norman Foster; he definitely was not an architect without a name.

However, there is more to the job of an architect than graphical talent. When someone wants to bring his visions into practice, the architect is not a free artist any more – he serves his customer, his client, has to communicate with him, look for compromises acceptable for both parties. And that is something Kaplický never wanted to do – compromise. That is why so many of his visions and ideas are just on paper. They were an inspiration to many, which could, and probably also did, lead to Kaplický’s deep feeling of fatal injustice: those inspired by him build projects, he does not. As time went by, this professional bitterness was deepening to some degree, even when his own Future Systems studio was operating. He founded it with David Nixon in 1979 and soon his work became a bottomless fountain of amazing ideas and stimuli directed deep into the future, yet they were not utopian. Kaplický and Future Systems took part in many award procedures and created an immense number of studies – and had no project implemented for fifteen years. It is a very stressful situation for an architect. This job is usually picked by those who want to see houses, areas of their designs, people who use them and like them. Designing works to be kept in drawers, it must be desperate for each architect, just like getting numerous prizes in contests, but never the first prize, which gives him the right to go through with the project. For example in the contest for the French National Library, Kaplický was so close to success – and Paris may be sorry today that French President was too patriotic in his choice at that time.

The causes of this lack of implemented projects were interesting. The architect, who left an incomplete, distinctly functionalist family house of a strictly cubistic shape behind him in Prague, was gradually getting out of his high-tech inebriation to richer shapes. They obviously found inspiration in the nature, but not in the spirit of bionics, but rather in the maximum relaxation and enchantment with the possibilities to create a world of dreamy, fanciful nature – thanks to the most sophisticated technology. Yet all of Kaplický’s works show respect to nature as well as a feeling of necessity to design environmental buildings. At least in theory.

At the end of the 1980s, the visionary approach of Kaplický and his Future Systems started celebrating success. First a family house in London, then a fragile floating bridge at West India Quay, found just at the border of the banking architecture of London’s new Docklands and the romantic, loosely reconstructed architecture of the old industrial docks. And then huge success with NatWest Media Centre at the Lord’s cricket stadium: a news platform hovering above the playing field, as if coming from another world and surprisingly eyeing this strange, traditional English game… And its aluminium shell, first of its kind in architecture; for the first time Kaplický here introduced his visionary hi-tech architecture with excellent purity and impressiveness. In 1999, he obtained the Stirling Award for it.

At that time he had had a huge exhibition. It was first introduced in London, and then in the National Gallery Prague, specifically in the Fair Palace, thanks to Zlatý řez and Michaela Kádnerová (and the generous sponsorship of Sipral). This was the first ever individual exhibition of a living architect in the National Gallery, and it was extremely successful. The models of unusual shapes and unexpected colours were a huge surprise and became a great attraction, just like the architect’s lecture. At that time, the environmental movement South Bohemian Mothers even wanted to ask Kaplický to design ecological houses that would help them in their fight against the Temelín nuclear power plant.

It is strange that this exhibition is never reminded anywhere, and Kaplický himself did not talk about it too much. As if this exhibition in the Czech Republic, received with much acclaim, did not fit in with his attitude, slightly injured, of an architect not understood by anyone at home. (It could be also partly caused by the fact that in 1995 the National Gallery negotiated with him the possibility that he could represent the Czech Republic at an international architectural exhibition in Venice in 1996; however, the negotiations did not succeed because of the high financial demands of the architect’s visions).

It also has to be mentioned that Kaplický often had lectures in the Czech Republic. And he always had an attentive audience, at least partly dazzled by his ideas. On the other hand, he created many enemies with his lectures here, because they had the same, repeated scheme – first demonstrations of Czech functionalistic architecture that in his eyes had a high quality, then a scorching criticism of everything built in the Czech Republic since the beginning of the 1990s (he did not take the years before into account), and then his own visions. It also explains why Kaplický was looking for builders for so long – he certainly was not a diplomat.

At the beginning of this century, Kaplický managed another great achievement in the UK – the Selfridges shopping centre in Birmingham. Even though the building is problematic for the shop as such, for example there are no shop windows, its shape and size are extremely attractive. But not in a positive sense. In a poll some time ago it was chosen as the ugliest building in the UK, but on the other hand it won the prestigious RIBA award in 2004. Some time later, however, Kaplický himself questioned some of its qualities – the use of advanced technology, its environmental character.

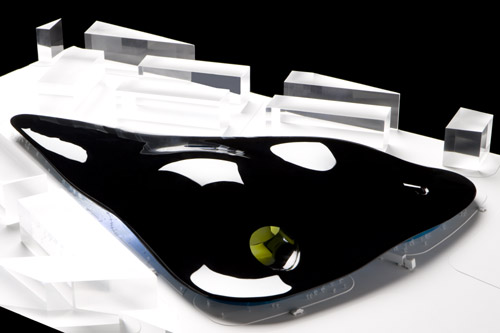

In our context, however, Kaplický’s most important feat is his “Prague” vision – the National Library project. However, I will not talk about it here – among other things because I do not see it as well-done within the context of Kaplický’s other works for many reasons and I do not think it is unfortunate that Prague will not have it. However, Museum Ferrari in Modena will be completed according to Kaplický’s design this year and his projects for a concert hall in České Budějovice and a small house near Benešov could be also implemented. If this goes through, it will not be easy – Kaplický was such a strong personality that even if he left completely prepared implementation plans, everything will be different without his direct participation in the construction.

Regardless of the number of implemented projects, Jan Kaplický was a great architect – one of the few exceptions that managed to move the development of architecture forward just by the strength of his ideas. His sketches and projects are part of the golden fund of contemporary architecture.

Jagg.cz

Jagg.cz Linkuj.cz

Linkuj.cz Google Bookmarks

Google Bookmarks Live bookmarks

Live bookmarks Digg

Digg Del.icio.us

Del.icio.us MySpace

MySpace Facebook

Facebook